Interview with Robert Saxton

Austin Boothroyd is talking with the distinguished British composer and academic Robert Saxton (b. 1953). Robert lives in London with his wife, the soprano Teresa Cahill.

Robert, I know that you’re really happy at the moment to be writing for ViolaViva. The publisher has a

London in June 2025

Yes. My father’s family, on one side, his father’s side, came from Russia and Lithuania, from the Jewish communities there. They came to UK at the end of the nineteenth century. As for my mother’s family, they all came from Europe, arriving in London from Hamburg in the 1830s, in 1838 I think, and her father arriving from Poland, he was born in the late nineteenth century in the Jewish quarter in Krakow.

Can you give me their surnames?

Yes, my father’s family, going back, were called Sachs, and in the UK this was changed to Saxton, because they anglicised it. Saxton is the name of a village. An interesting connection here is that my father’s mother, who was Church of England, came from Yorkshire, and this is where, coincidentally, the village of Saxton is located.

And your mother’s paternal name?

Infeld, which was anglicised to Infield, and that was because her father, who was a mathematician and, later, a statistician, was, as a young man, working in the civil service during the First World War, and they said could you anglicise your name please because of the problem of having a German name during war time!

Interestingly, their lineage traces back to artisans and scholars, which I like to think has influenced my affinity for creativity and intellectual pursuits. It is rather humbling to reflect on how these European connections, steeped in both hardship and resilience, have contributed to my own journey in music and academia.

My grandfather’s first name was Louis and I was partly named after him; one of my middle names is Louis. He unfortunately died before I was born, but one of the last things he was involved in as a statistician was in the setting up of the National Health Service at the end of the Second World War. I have a wonderful photograph of him posing with Aneurin Bevan, the secretary of state at the time for health and social care.

I’m wondering also about your love of music: were your mother and father musical?

Both loved the arts and took my sister and me to concerts, art galleries and, above all, encouraged us to read widely. It was my father’s parents who were musical; my Yorkshire grandmother was an excellent pianist and my grandfather was a trained amateur singer. My sister Vivienne became a dance teacher and examiner and was trained at the Royal Ballet School. This has certainly influenced me as I grew up with it. She was in a masterclass with Léonid Massine, the Russian choreographer, so has been in touch with the Great Tradition.

Can you tell me about your early experiences of working in Europe?

My first ever professional performance was at Hilversum Radio in Holland at the Gaudeamus Muziekweek. I won

photo of Sir Michael

Tippett (oldest composer

at the Proms) and RS

(youngest composer at

that year’s Proms) with

the bust of Sir Henry

Wood (founder of the

Proms) (early 1980s)

I then had a performance at the Beethovenhalle in Bonn as part of the International Society for Contemporary Music in 1977. And it was a piece based on a Hermann Hesse novel, ‘Narziβ und Goldmund’, played by the Deutsche Radio Philharmonie Saarbrücken conducted by Hans Zender. I had the same piece, ‘Reflections of Narcissus and Goldmund’, played at the Royan Festival (also called Un Violon sur le Sable) in South West France by a Dutch ensemble. It was played in the Casino, which thankfully had been cleared of gaming tables to make space!

Tessa and I, at this time, also worked behind the Iron Curtain in Europe. Tessa sang in East Germany and in Poland and I was ‘sent’ by the Composers’ Guild of Great Britain, just after my postgraduate degree, with Jonathan Harvey, composer and professor of music at Sussex University, to East Berlin. To this day I have never been to the West side of Berlin, but only glimpsed it from my East German Composers’ Union apartment on Unter den Linden across the Berlin Wall. I was somewhat shaken when my minder, Fraulein Jelena Fischer, asked me about my maternal grandfather being born in the Jewish quarter of Krakov… I asked how she knew this and she said: ‘Oh, I know everything about you!’ Creepy…

And both Tess and I have worked at Hans Werner Henze’s festival in Montepulciano, the Cantiere Internazionale d’Arte. In Italy I also sat on the jury for a choral competition in Arezzo, the International Polyphonic Competition Guido d’Arezzo, and in Swizerland as a jury member for a competition in Bern or was it Basel?

Closer to home, in France, I had a piece called Traumstadt, based on a painting by Paul Klee, performed by the Nouvel Orchestre Philharmoniqe de Radio France in the 1980’s.

You learned the violin as a young boy. Can you tell me about your lessons, where you took them, with whom and what you played? What were the lessons like?

My first violin teacher was from my school and was also my mathematics teacher. He didn’t believe in children aged eight or nine doing hundreds of exercises, and putting you off, in his opinion. So I started by learning syllabus pieces listed by the Associated Board of the Royal Schools of Music and the Bach A minor Violin Concerto! And literally note by note, once I had learned the basics, I memorised the fingerings of the concerto and started to play. His name was Anthony Cleveland and later in life he gave up teaching and joined the BBC Symphony Orchestra. When I went to boarding school I had a violin teacher who had studied with Max Rostal; that was Peter Chamberlain. He said to me ‘I don’t agree with this’ and took me back to basics with my bow hold and taught me Ševčik. And it was probably good for me. I played a lot in school orchestras and often led the second violins playing a wealth of repertoire. My boarding school was Bryanston School in Dorset. It had a strong music tradition; Mark Elder, John Eliot Gardiner, Mark Wigglesworth and Simon Standage were also pupils there.

But, from an early age, you were also very interested in composing. Your mentors and teachers included Benjamin Britten, Elisabeth Lutyens and Luciano Berio. Do you continue to feel their influence in your writing today, or indeed the influence of your other teachers, or would you say that your music has moved on from these influences?

That’s a brilliant question. Yes and no. I always feel the need to make the most of my opportunities, partly because of my parents' inherited sense of the importance of hard work and desire to immerse themselves in what was still a new country for my family. I feel the Britten influence at a very, very deep level. He’s always there. I was 11 years old, was with him in his studio. He was the first professional composer I had ever met, I’d already loved the opera Peter Grimes, and his advice and encouragement was bound to leave a lasting impression. When I went to Elisabeth Lutyens, I was now 16, she quite rightly said ‘that’s enough of this nonsense, you’re not going to write Peter Grimes’, and so we got down to work. To be fair, Britten had already written a testimonial for me which said that I now needed first class tuition and that unfortunately he was too busy to provide this. Lis Lutyens was wonderful for four years, and for more than just composition, she almost became a second mum to me. She was very tough as a teacher, very strict.

Did you study strict counterpoint with her?

I did that later at Cambridge University with my teacher there, in my first year as an undergraduate, for harmony and counterpoint, who was David Willcocks. And my director of studies was Peter le Huray, who was a

Rostropovich and RS after the

premiere of Saxton’s Cello

Concerto at the Barbican Centre,

London, London Symphony

Orchestra conducted by

Knussen (early 1990s)

And Luciano Berio I went to during my postgraduate studies. Robert Sherlaw Johnson had taken me as a postgraduate at Oxford University (he was a Messiaen scholar, a very fine composer and a virtuoso pianist who made the first commercial recording of Messiaen’s Catalogue d’oiseaux). But Berio was a very different kind of teacher. He very generously saw me on and off for two or three years, always in various bars or restaurants in London. He spoke very good English and was passionate about his craft. He would look at a score for 20 minutes in silence and then he would suddenly look up and say ‘what do you mean?’ And he would either answer it himself in an incredibly musical and technical way or, on another day, he would say ‘have you no brain? Go’. And you’d get up to go and then he would say ‘why are you going?’ and you would say ‘you told me to go’ and he would say ‘don’t be silly, sit down!’ That’s literally true!

But providing continuity at Cambridge and Oxford were two teachers who were both fantastic mentors and guides during these formative years. One was Robin Holloway, who was my composition supervisor at Cambridge, and the other I’ve already mentioned, Robert Sherlaw Johnson, my postgraduate supervisor at Oxford. I should add that I have always been profoundly inspired by the great English heritage of choral music from the 15th and 16th centuries and have written several works for Church of England use.

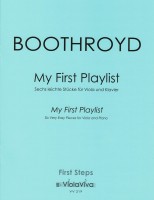

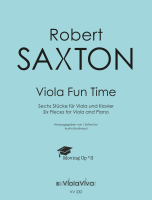

You have written two volumes now for ViolaViva’s educational catalogue and, happily, a third volume is on its way, all for viola and piano. The first two volumes feature in the First Steps Series and the Moving Up Series while the third volume is being prepared specifically for the Mastery Series: they are titled Viola Play Time (VV 229), Viola Fun Time (VV 232) and Viola Show Time (VV 236). What appeals to you today about writing for learners of the viola?

Well, I spent 43 years teaching, I loved my students and I loved teaching. I remember when I was working at

Robert’s wife) and the

conductor Christopher

Austin rehearsing Act

Two of Robert Saxton’s

chamber opera Caritas

(commissioned originally

by Opera North) with RS

speaking to them.

(late 1990s)

Finally, turning to your extensive and outstanding career as an educator in many leading musical institutions in the UK - the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the Royal Academy of Music and Worcester College Oxford. And, in your capacity as Composer-in-Association at the Purcell School, I know that you recently wrote an ensemble piece for the students, to celebrate the 150th anniversary of Maurice Ravel - 'Le Tombeau de Ravel' - which premiered at the Wigmore Hall in May this year. I’m curious: there are many obvious differences in teaching and writing for advanced students as opposed to students who are beginners, but do you think that there might be similarities in your approach to writing for students working at these different levels?

It’s in the approach itself. So, when preparing to write for a student I’m trying to imagine what that person is, how they might think, how their heart beats even, how their mind works... For example, I used to do outreach work, for Glyndebourne Opera and for London Sinfonietta, sometimes in cash-poor state schools, and I did a spell as a composer in residence at Garforth Comprehensive School near Leeds, and what I found I was trying to do was to enthuse the students, first and foremost, and to find out what I could bring out in them. The approach and the purpose is therefore the same whatever the level. I totally believe in learning the basics of our wonderful art, which is doubly important for students now making use of and learning with the aid of new technologies. You must build your expertise from a solid foundation so that you fully understand where technology is really helping.

Several years ago we had a visit from an Arabic classical musician, Issa Boulos, and we were talking about this, and we both felt that to fully understand our different traditions, European classical music and Arabic classical music, that it was the foundations of our different languages that mattered the most. If you learn to think and understand deeply what you are doing, then you can much more easily and fruitfully address other traditions, because your mind is professionally trained.

Robert, thank you for sharing all these points, your thoughts and your memories with us.

Not at all.

London, 12th June 2025

Robert Saxton is represented by, and can be contacted at, Liz Webb Production and Management.

Silverthorne Paul wrote on 05.07.2025 at 10:08

It's a pity the article doesn't mention the wonderful viola concerto Robert wrote for me. I gave is first performance in 1986 and gave further performances in the UK and Finland in the following years up to a performance at the BBC Proms in 1993. It remains one of the most difficult pieces I've ever played and I reckon I would not have had the career I have had without the technique and skills I gained in the months I spent overcoming the challenges of this work. Thank you Robert!

Educational Series

|

» to the edition with preview (#1)

» to the edition with preview (#2)

» to the edition with preview (#3)

» to the edition with preview (#4)

Educational Series

|

» to the edition with preview (#2)

Educational Series

|

Three further editions in the Mastery publication series are in preparation and will be published until November 2025:

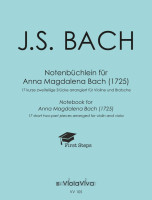

- J. S. Bach

for Violin and Viola

(VV 110, Mastery #2)

- Eric Mayr

for Clarinet in B, Viola and Piano

(VV 333, Mastery #3)

- Robert Saxton

for Viola and Piano

(VV 236, Mastery #4)

Viola Newsletter |

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our monthly viola news letter will keep you informed.

Do you don't want to miss any news regarding viola anymore? Our monthly viola news letter will keep you informed.

» Subscribe to our viola letter for free

|

|

Visit us on Instagram and don't forget to join our music community and share your thoughts about the composer or any other viola-related ideas!

Visit us on Instagram and don't forget to join our music community and share your thoughts about the composer or any other viola-related ideas!

» Music4Viola on Instagram

|

|

Visit and like us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.

Visit and like us on Facebook. The news articles are also posted.

» Music4Viola on Facebook

Happily, Robert's viola concerto is mentioned in the preface to each of his ViolaViva educational catalogue publications: Viola Play Time, Viola Fun Time and Viola Show Time.

Robert sent an email in response which says 'Any chance you could add the Viola Concerto and Paul Silverthorne (who was principal viola of the London Sinfonietta and LSO)? The Viola Concerto is dedicated to the memory of Benjamin Britten, who was a viola player. I wrote a work for him for viola and piano: Invocation, Dance and Meditation.